The way we understand the world is shaped not just by what we see—but by what we’re shown. News media follow a specific logic for deciding what gets reported and what doesn’t. And what’s left out might be just as important as what makes the headlines.

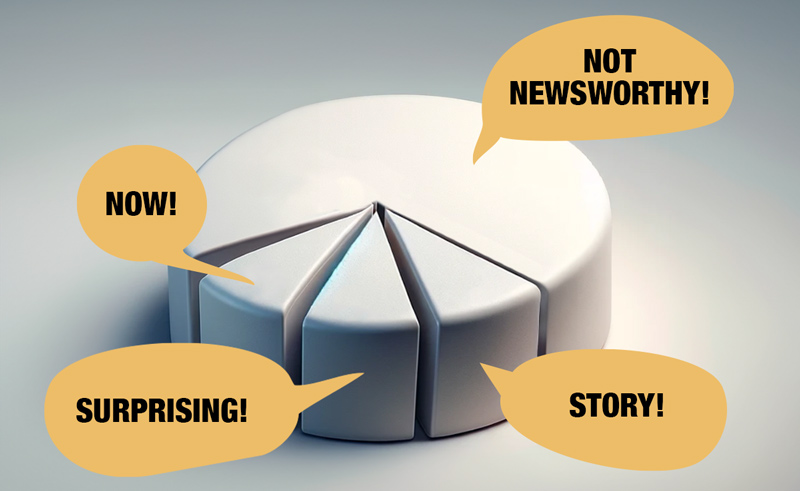

Imagine the world as a giant cake, representing everything happening right now. What do the news media report? Only three small slices of that cake: what’s happening right now, what’s surprising, and what fits into an understandable story. The rest of the cake—the overwhelming majority of what’s actually occurring in the world—doesn’t fit into the logic of news reporting, so we rarely get to hear about it.

Many people develop a skewed perception of reality precisely because news coverage only includes events falling into these three categories. It would be easy to blame journalists and editors for this, but ultimately it’s just a consequence of human psychology.

What’s happening now captures our interest far more than what happened yesterday. The surprising is infinitely more engaging than everyday events. And a clear, coherent story with obvious villains, heroes, and victims is much more satisfying than a complicated tangle of actors—especially when the conflicts stem from systems and structures rather than individual actions.

This is precisely why it’s much easier for news media outlets to point fingers at an individual accused of questionable morality rather than try to explain a complex system that encourages certain behavior.

For instance, think about how the media often portray wealthy individuals who profit from perfectly legal but morally controversial practices—such as running private prisons, operating gambling companies, or managing high-interest payday loan services. They’re often depicted as greedy and immoral, as if the root of the problem were their personal character. But if these individuals follow all existing laws and regulations, is the issue really with them personally? Or is the real problem the politically designed systems and regulatory frameworks that allow—even encourage—these outcomes? Addressing that question thoroughly would require in-depth journalism, and most readers would probably scroll past such a complicated story anyway.

Of course, there’s a difference between various types of media. But even reputable outlets—the kind we typically expect more from—are governed by this same news logic. That’s why they often fail to truly inform us about the world. Those three small slices of cake—what’s happening now, what’s surprising, and what makes a compelling story—are all we receive. Everything else remains invisible.

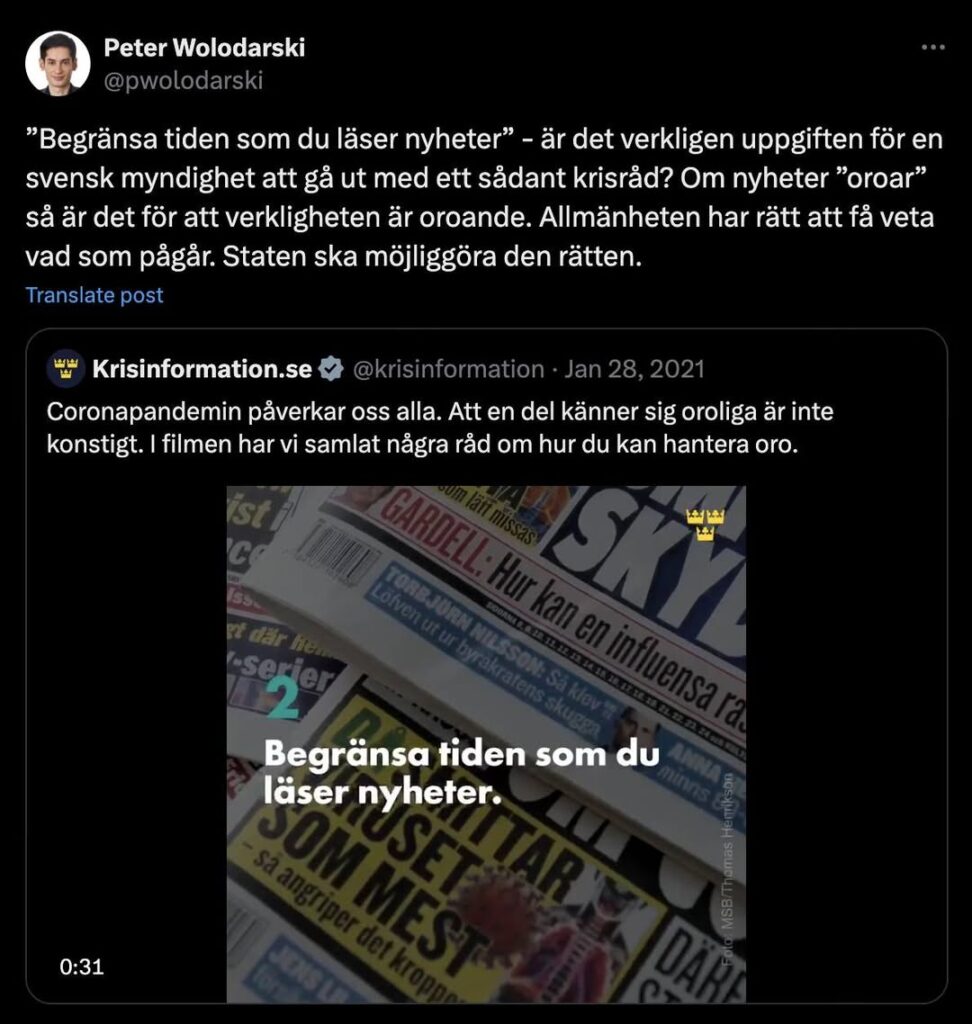

This becomes especially clear when respected journalists argue that news reporting reflects reality. Take, for instance, Peter Wolodarski, editor-in-chief of Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s largest daily newspaper, widely considered to be among the country’s most prestigious media outlets. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Wolodarski publicly challenged a Swedish public health authority’s recommendation to “limit your news consumption” in order to reduce anxiety. He argued that if the news makes people anxious, it’s simply because reality itself is anxiety-provoking. But this is where he gets it wrong.

Swedish journalist Peter Wolodarski criticizes a government agency for advising people to “limit the time you spend reading the news” during the COVID-19 pandemic, arguing that if the news is disturbing, it’s because reality is disturbing—and that citizens have a right to know what’s going on.

Reality is far bigger than what fits into news reporting. Those three small slices—what’s current, what’s surprising, and what fits a neat narrative—are merely fragments. News doesn’t convey everything; it conveys only what fits into its logic.

Claiming that news coverage accurately reflects reality is like believing three slices of cake make an entire cake. They don’t. Or it’s like peeking through a tiny keyhole and assuming you’ve seen the whole room. Certainly, what you see through the keyhole is real—but it’s an extremely limited perspective, carefully selected to fit the logic of news selection. The rest of the room—less dramatic, more complex, and harder to communicate—remains invisible.

My intention here isn’t to criticize Wolodarski personally. But on this point, he is mistaken—and I’m correct.

To understand why news reporting works this way, we need to examine the underlying principles guiding what becomes newsworthy. Those small slices of the cake are limited, and what fits within them follows certain clear patterns. The logic behind news reporting isn’t random—it’s governed by three simple principles that determine what makes headlines and what gets left out.

Tobias Wahlqvist

I write to make sense of a world that’s too often distorted by speed, simplification, and noise. My focus is on how the daily news cycle affects our minds, our understanding, and our ability to think clearly. This work grows from a deep need to see connections—between systems, behaviour, and meaning—and to share those insights in a way that’s accessible without being superficial. I believe that calm, clarity and curiosity are underrated forces in today’s information culture.