This text was previously published at Warp News

The news presents itself as informative—but it isn’t. Its invented conflicts don’t empower us; they make us less capable of action and less truly informed. These manufactured opinion wars are fought by volunteers. You can opt out.

You know the situation. Someone is making a point—maybe online, maybe in the break room, maybe even at a family gathering—and they’re clearly, wildly wrong. They’re saying something offensive. They’ve completely misunderstood how something works. Or they’re drawing insane conclusions that defy all reason and logic. And there you are. The last outpost of reason and sanity. Someone has to object!

Sometimes you feel like the chosen one, the one who has to do it. Like it’s your responsibility to step in, correct the conversation, and clear up the misunderstandings and falsehoods. You see baseless claims and feel they can’t be left unanswered. You don’t want to walk away.

I used to feel that pressure a lot. But it’s exhausting. And it’s also pretty thankless—very few online arguments end with someone admitting the brilliance of your reasoning and changing their mind, in my experience.

These days, I more often manage to resist the urge to get involved. And I feel better for it. If I do walk away, then that’s what happens—because while it’s important to help steer the world toward a saner course, it’s also important to protect my own state of mind.

It’s irrational to respond to everything

It’s also quite irrational to jump into every debate. The only arguments worth having are those where there’s a chance—however slim—that you might actually shift someone’s thinking. And that probably only happens in the tiny fraction of cases where you weren’t too far apart to begin with, and both sides are somewhat open and curious. In other words, the debates most likely to be productive are the ones that provoke you the least.

Sure, you might want to respond out of concern for the bystanders—the less invested observers who are following the debate quietly. Maybe your comment will help prevent them from being misled. But even that has a downside: by replying, you’re often amplifying the original post, giving it more reach. You risk giving nonsense a platform.

Most people eager to argue aren’t looking to weigh pros and cons or get closer to the truth. They’ve already made up their minds. What they’re looking for is to preach their beliefs, show allegiance to their in-group, and distance themselves from the out-group. And yes, it feels good to craft a well-worded, logically airtight reply with solid sources—one that really puts that little idiot in their place. It feels like a win.

The problem is, it never works.

The backfire effect

The satisfaction of “shutting down” your opponent has nothing to do with whether they actually change their mind. In fact, it often triggers the opposite: a psychological response known as the backfire effect, where people double down on their mistaken beliefs the more forcefully they’re challenged.

The economist F.A. Hayek once noted that people treat their opinions as their dearest possessions—so being persuaded feels like a kind of theft. No, minds don’t change through brute force. Opinions shift quietly, over time, and on one’s own terms—not because someone steamrolled you with facts and logic.

A more effective approach is to ask open-ended questions. Sometimes, that can plant a seed—one that might grow into a new thought days or weeks later.

Media logic

Still, we seem addicted to treating debate like a kind of intellectual mud wrestling, where everyone gets dirty and no one gets wiser. We’ve built entire social media platforms (Twitter!) and prime-time TV formats (Opinion Live, Sweden Meets) around verbal entertainment violence as a central concept.

That’s how we work. And that’s how media logic works too.

Suppose thousands of researchers jointly publish a report with conclusions on an important issue. Not every scientist agrees on every detail, but there’s a broad consensus. No real conflict. Great—but from a media perspective, completely boring. Not something that grabs attention. It won’t drive clicks and probably won’t even make the paper.

To create engaging content in that situation, the news machine has to ignore the consensus and go looking for a dissenting voice—someone to play the challenger. That’s not hard to find. For almost any imaginable position, there’s someone out there shouting into the void, happy to receive free airtime. It’s dishonest toward the audience. But it works.

The alternative perspective is often presented by someone with an impressive title like “scientist” or “professor”—not necessarily with relevant expertise, but enough to seem credible to a layperson. And because ideology often comes dressed in facts, it’s hard to tell what’s genuine expertise and what’s motivated reasoning. A common trick is to present factually correct information while leaving out or downplaying key factors. This creates the illusion of a meaningful conflict between a broadly unified scientific community and a few contrarians. In fact, the official goal of Sweden’s public debate show Sverige möts is to “actively bring together people with strongly polarized views on controversial issues.”

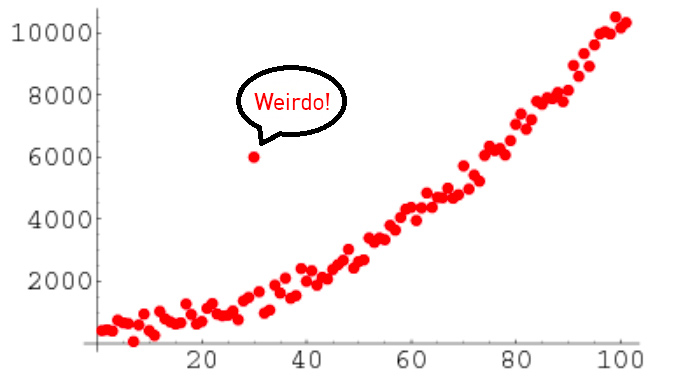

Outliers are clickbait gold

In statistics, we call those fringe voices outliers—and remove them to strengthen the overall result. We filter out the outliers to clarify the picture. In news journalism, it’s the opposite: they’re brought in, labeled “independent experts,” and invited to participate in prime-time TV debates alongside their ideological rivals for two intense minutes of shouting and spectacle. It’s popcorn-friendly—but gives a very skewed sense of reality.

The thoughtful, meaningful conversation could have taken place between humble voices in the middle—those who complement each other’s perspectives. Instead, we get the extremes, disagreeing on everything. Knowledge reduced to gladiator combat. Maybe it’s entertaining. But it’s not informative.

The news sets up conflicts where the parties stand far apart—because contrast is easy to recognize, even when it’s meaningless or false. They need simple caricatures, just like the traveling theater troupes of the past, who drew in their audiences with a recurring cast of exaggerated characters in the same loud costumes and with the same one-dimensional motives. News outlets need their caricatures for the same reason. Just like the troupes, the media’s spotlight doesn’t stay on one place for long. New and complex topics are always emerging, and each news cycle needs to package them fast. To avoid losing the audience in all the details, at least the narrative structure has to stay familiar. The structure of polarization. A structure we all recognize. One that drives engagement.

The high pitch comes at a cost

Since news thrives on conflict, it also creates conflict where none is needed. A neutral report doesn’t generate much engagement. A report that threatens someone’s worldview? Much more engaging—because no one wants to back down. Readers feel the urge to step in, to take sides in the conflict. Without realizing it, they become foot soldiers in the publishers’ campaign for “engagement.”

Some use the fringe voice as a weapon to attack someone they dislike politically. Others are outraged that the extreme view was even given a platform, and jump in on the opposite side. The article gets commented on, shared, and angrily dissected. The newsroom takes note: the piece generated engagement. “Let’s do more of that.”

And so we end up wasting time and mental energy shouting at each other from opposing trenches (dug for us by the media), lobbing our respective articles and outlier-expert quotes at each other like hot air grenades. It becomes about as productive as arguing over which football team is best. NATO or neutrality? Nuclear power or wind? There’s an expert for every position. Choose your fighter. Get in the trenches.

Studies show that when politics is framed as conflict instead of problem-solving, those who dislike conflict withdraw, while the combative are drawn in. Treating discussion as a fight becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

What if we’re not really that divided?

It seems like everyone’s fighting all the time. Just take a stroll through Twitter and observe the tone. But what if we’re not actually that divided? What if most people just don’t want to surrender in the media’s manufactured conflicts? Twitter may be on fire, but the fuel is often news articles written from partisan perspectives far removed from the broader consensus.

Journalism needs to take greater responsibility here—by clearly showing where the weight of opinion lies within a field, instead of chasing provocative quotes that grab attention. Filter out the outliers. Stop performing this overacted theater of effects. And we, the news consumers, need to take responsibility too. Every time we click a headline, share something just to point out how wrong it is, or join a troll-fueled comment war over a sloppy article, we reward the content. No wonder newsrooms keep producing poor journalism if we keep feeding it.

To move forward, we need more shared perspectives—bridges across disagreement. That requires, at the very least, resisting the urge to amplify nonsense. Sometimes we have to sit on our hands instead of pointing fingers. Even when someone is wrong. Especially when someone is extremely wrong. Because if we don’t, we risk contributing to the avalanche of outrage and counter-outrage that buries the constructive conversations still happening, somewhere in the background.

And because we risk becoming nameless soldiers ourselves, caught in the trenches of news-driven conflicts where everyone loses.

You can opt out of the manufactured opinion war

Despite the trenches, we live in a world that is improving in many ways. But there’s still work to do. Things we can make better. That takes action and real knowledge. The news claims to inform—but it doesn’t. Its made-up conflicts leave us less capable, not more.

There’s a wealth of meaningful insight and worthwhile conversation out there. When we let the news noise fade, it gets easier to find it. And even if you don’t want to quit the news entirely, you can still gain a lot by becoming more aware of how you consume news—and what you reward with your clicks.

The opinion war is fought by volunteers.

You don’t have to take part.